| AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION by Georgios Agelopoulos |

Georgios Agelopoulos

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION

by

Eleftheria Deltsou

Aigli Brouskou

Social Anthropologists

*Prefecture of Thessaloniki, Greece: Center for the Study and Development of the Greek Culture of the Black Sea

*Sponsor: Greek Telecommunications Organization (OTE)

*With the cooperation of the Community and of the Cultural Association of Nea Messimvria,

as well as of the people of Nea Messimvria and of Nessebur in Bulgaria

*Research team can be reached by email at (gagelop@botsalo.physics.auth.gr) :

* Photography by Angeliki Avgiitidou

*Web Design by Anthony Patrinos, (patrinos@hyper.gr) Computer man

Table of Contents

The village of Nea Messimvria in the Balkan context

Messimvria in Bulgaria, the contemporary Nessebur, is a coastal town of the Black Sea, built on a small peninsula in the sea and connected to the mainland with a narrow piece of land. In the summer and autumn of 1925 the Italian ship "Gabriella" transported 340 Greek families from the Bulgarian town of Messimvria to Greece. This transfer of Messimvrians from Bulgaria to Greece took place in the context of a voluntary exchange of populations, which occured in the Balkan countries in the beginnings of the 20th century, as part of the process of the creation of homogeneous nation-states. A number of approximately 100 families of Greek Messimvrians decided not to leave Messimvria and were gradually incorporated in Bulgarian society. The Messimvrian refugees, who came to Greece, settled at the community of Bugharievo (29 kms. west of Thessaloniki), which was later renamed as New Messimvria.

For Messimvrians in Greece, the establishment of a new hometown and the hardships of refugeeness became parts of their collective identity. A fundamental part of this identity, however, and a primary point of reference, was and is the town of Messimvria in the Black Sea. From 1925 to the present the relationships and the communication between the Messimvrians in Greece and those who stayed in Nessebur were maintained and re-instituted in many different forms. With periods of easier and harder access to each other (the hardest of all being from 1939-1957), communication and the relationships among them acquired different expressions.

Messimvrians boarding Gabriella on August 1925

This exhibition shows various aspects of the Messimvrian identity in Greece, as these are expressed in the different forms of communication, which were established between the two places and between the two people, in Greece and in Bulgaria. The aim is to demonstrate these forms of communication, of relationships, of continuity, and of change between the towns of Messimvria (Nessebur) in Bulgaria and of Nea Messimvria in Greece.

The research for this exhibition was conducted by a group of social anthropologists in the summer of 1996 in Nea Messimvria, Greece, and in Messimvria (Nessebur), Bulgaria. Based on this research an ethnographic exhibition takes place from November 14th to December 6th of 1996 in the Cultural Center of the Prefecture of Thessaloniki. The material presented at this WWW site is part of this ethnographic exhibition. The exhibition and its presentation at the WWW site do not offer an overall theoretical documentation of the studied case. This WWW site is a synopsis of the project and the exhibition, aiming to a comprehension of the experiences of the Messimvrians by a wider audience. ![]()

The development of any kind of communication requires first of all the existence, and/or the construction of relationships. In fact, there can be no communication without the prior existence, or the formation of relationships. In that sense, communication becomes almost co-terminous with the existence of relationships, which in turn rely on the actuality of different kinds of bonds. Communication is not merely when people write or talk to other people, who are, or are not in the vicinity. Communication is also what people see, and let others see in them, as to who they are.

In Nea Messimvria everyday forms of behavior, discussions, visits to Bulgaria, contacts with people there, etc., all rely on the prior existence of relationships and on the present mobilization of memories. The "stories" about "life there in Messimvria" are part of people's everyday lives in Nea Messimvria. Objects which were carried from "there" (holy icons, pieces of furniture, trousseau items, objects of household use, jewelry, etc.), as well as the technical knowledge of cultivating vineyards and making wine were transported from the old hometown to the new one and became an intangible form of contact with, and the point of reference for, what they left and what they rediscover there now in their visits.

What people in the Bulgarian Messimvria and in the Greek Nea Messimvria do today, 70 years after they were separated, constitute common cultural places, which not only provide the basis for communication, but they are communication in themselves. This exhibition displays that people's everyday lives constitute ways of remembrance, which are not just memories for the older ones, but create relationships for the younger ones. Objective of this exhibition is to present the relationships which existed, or which were created between the two places and which were, for the people who inhabited them, then and now, simultaneously both present and absent. The exhibition demonstrates how communication, continuity, but also change are constructed not only in proximity and in the facility of reaching easily the other side, but also in conditions of distance and of absence. It is in all these senses that this exhibition demontrates the communication between the Greek Nea Messimvria and the Bulgarian Messimvria or Nessebur. ![]()

Messimvria has a continuing history throughout the centuries. In antiquity it was one of the ancient Greek colonies established in the Black sea by the metropolis of Megara. In the Byzantine times it was a significant fortress-port and the place of exile for nobles, as well as the place where a unique iconography and church architecture developed. During the following centuries, Messimvria was periodically taken by Bulgarian rulers and by the Ottomans. In the Ottoman times and later, the largest part of Messimvria's population continued to be "Romii" (i.e., Greek speaking Orthodox). In the end of the 19th century, Messimvria became part of the independent multi-ethnic state of Eastern Rumelia, and in the beginnings of the 20th century it was incorporated in Bulgaria.

<- The Byzantine church of St. John the Baptist (Velkov, 1989)

![]()

For the Greek Messimvrians the days of the Eastern Rumelia state were the last glimpses of a blooming life. In the end of the 19th century and until 1906, Messimvria was a community with a Greek local administration, the seat of a Bishop affiliated to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, it had its own Greek educational institutions. People in Messimvria were then economically and socially closely connected to the other Greek communities of the Black sea. The integration of Messimvria, as of the whole of Eastern Rumelia, in Bulgaria marked the end of the above situation.

Messimvrian bourgeois in the early twenties

After 1906 the Greeks of Messimvria started experiencing the new political reality of a Bulgarian nation-state. The Greek schools of Messimvria were closed and children attended only Bulgarian schools. As Bulgarian citizens, during the Balkan wars and the first World War, Messimvrian men served in the Bulgarian army, often fighting against the Greek army. For the Greek Messimvrians this was a hard experience.

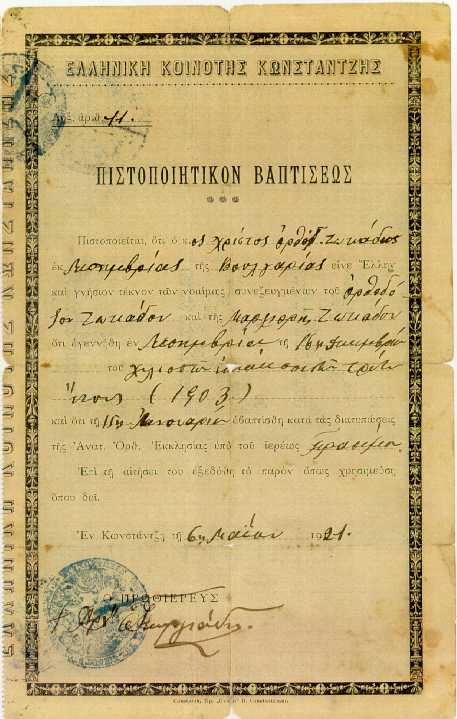

Baptism Certificates of Greek Messimvrians issued at Messivria and Constanza dating from the beginnings of the century

Despite the new political reality, Messimvrians continued the economic activities that they had and their bourgeois everyday lives. Commerce, wine-production, fishing and shipping were the mainest of their economic practices and they carried them on with zest. The economic ease of the Messimvrians enabled them to have a western European bourgeois lifestyle, which they kept until the time of their departure in 1925. This lifestyle included trips abroad, as well as western European forms of entertainment and of conspicuous consumption. ![]()

For the Balkan countries of the first quarter of the 20th century, the effort to create homogeneous nation-states with no ethnic minorities inside their borders, led to the exchange of populations among them. The Greeks of Messimvria were not excluded from this process. In 1925, and in the context of the treaty of Neuilly (1919), Messimvrians "voluntarily" decided to move to Greece. In August and in October of 1925 the steamboat Gabriella carried the majority of the Greek Messimvrians to Thessaloniki, Greece. Only a number of about 100 families decided to remain in Messimvria (Nessebur), where the Greek population that left was replaced by Bulgarian speaking refugees from Greek Macedonia. The exchange of populations was overseen by the Society of the Nations, while the exchanges of properties followed the provisions of the treaty of Neuilly. For all the Greeks who left, the departure was a painful ordeal, which was imprinted not only on their memory, but often also on the last picture that they took in front of their houses.

"Our last picture in our home-town Messimvria of Efksinos (Black Sea) at the day of the migration 22-9-1925 [...]" ![]()

The vast majority of the Messimvrians who left Bulgaria and came to Greece, settled in Bugharievo, a village of farmers and shepherds, 20 kms west of the city of Thessaloniki. Messimvrians, in exchange of the houses and the properties that they left in Bulgaria, were given by the Refugees Settlement Commission money and land, while they personally undertook the building of their houses. Before 1912-1913, the community of Bugharievo, which was later renamed as Karavia and even later as Nea Messimvria, was inhabited exclusively by local Slav speakers, who then moved to Bulgaria, on the basis of procedures similar to those of the treaty of Neuilly. In 1922 the abandoned houses of the locals who left, were taken by Greek refugees, who came from eastern Thrace, and by Pontic Greeks from Kars of Caucasus.

House Evaluation and Transfer Protocol issued by the Refugee Settlement Commission in Greece

1926-1940 1940-1950 1950-1960 Couples with both spouses of Messimvrian origin 90 47 37 Couples where only one spouse is of Messimvrian origin 26 30 56

The coexistence of all those different groups of people within the same community initially became the cause of controversies and animosities among them. Main causes for controversies were the distribution by the local government of land for cultivation, of pasture land, of water, and of community funds. In the course of time, these issues were settled and the contentions evaporated. ![]()

The main economic activities characteristic of the life of Messimvrians in Bulgaria were fishing and the cultivation of vineyards. The significance of both becomes clear from the following dowry document of 1895:

Blessing of the fishermen's boats at the beginning of the fishing season

"... the parents of the bride promise to the groom and to their daughter ... a vineyard at the place alonia, ..., the right for [the produce of] two double fish nets in the middle season ...."

Fishing, however, was the activity that disappeared from the life of the Messimvrians when they settled in Greece. The sea, part of the landscape in the Bulgarian Messimvria, marked not only their lives back then, but also their departure, as it became the route to refugeeness. Since then, the sea has become a memory for the Messimvrians, who settled in the Macedonian plain.

Wine storage barrels in contemporary Nea Messimvria

On the other hand, the cultivation of vineyards and the production of wine is the activity, which the Messimvrians continued to practice ceaselessly. From the moment of their settlement in the village, they set up vast fields of vineyards and shortly Nea Messimvria became one of the most significant wine-producing villages of Northern Greece. The transfer of the economic activity that they knew best, and possibly loved best, became not only the means for their incorporation in Greek society, but also their way of familiarizing the place. Distillery in contemporary Nea Messimvria

![]()

An expression of the relationships between the two Messimvrias and their people is also what Messimvrians in Greece carried on doing, what they "carried" with and in them in their everyday practices, in their beliefs, in their activities. For Messimvrians, the ways they do things, from the more to the less significant, from the most formal moments of collective religious practices to the simplest everyday habits, all reveal the kinds of relationships which exist between the two places, while they create the relationships themselves. What people learn from their parents, what they embody in their behavior living in the context of a culture which was both transferred from one place to another, but also changed in the new conditions, are all ways of communication with the past and of formation of the present conditions.

Women's hand-made pieces of work were and are highly valued in Nessebur and Nea Messimvria

![]()

In the lack of physical proximity, what replaces its immediacy, what comes to replace physical presence, or the ability of communication, is memory. Memory joins people together, keeps bonds alive. And people's memories create imaginary and real places, in which people in Greece and in Bulgaria not only express their identities in relationship to a distant past, but organize their lives and establish relationships through them.

Grandmother's hand-made notepad

These memories are realized in the objects that the Messimvrians who came to Greece carried with them, or inherited from their parents or grandparents, in the values and in the forms of knowledge that they had, or acquired from their parents. When, however, people realized that year by year things get all the more distant, then the need to testify their own memories became urgent. An old woman in Nea Messimvria made a little booklet with her own hands and testified the place: the churches in Messimvria, the shops, the people.

Memory, nonetheless, while it realized Messimvria for those who wanted and want to remember, it also became a burden for those who wanted and want to forget the past and to move on. Several objects of memory (pictures, old pieces of furniture, letters, etc.) found their places in the basements of the houses, in the backyards, in bonfires. ![]()

One of the most significant ways that memory is created, kept alive and transmitted, is found in pictures. Pictures are significant not only in terms of what they show, but also in terms of what they mean for the people who have them, where they are placed, what is written on them. Pictures have multiple significances, as their meanings depend on all of the above. In all of the above ways, memories are realized into places of communication, and in all their material expressions they become not something about the past, but a thing of the present.

Picture from one of the first visits of Greek Messimvrians to Nessebur in the late fifties

During the first years of the separation until 1939 and then again after 1960, letters, cards, and pictures kept the relationships among Messimvrians in Greece and in Bulgaria alive. What was written on the cards and the letters was not merely pieces of information about their lives after the separation, it was the reconstruction of their relationships. The neighbor, the uncle, the aunt, the sister, the nephew, those idioms of past relationships, were reconstituted in the present of communication and became steady points of reference for their lives, which had radically changed. The discontinuities in people's lives, created by international politics, were re-established through the pictures they were sending to each other. These pictures embodied the continuity of life in the discontinuity of communication.

Picture of Messimvrians of Nessebur visiting Acropolis (Front) (Back)

After 1960, communicating with letters and phone calls became much easier. In those days Messimvrians from Greece visited Messimvria in Bulgaria for the first time after many years and celebrated the reunion with old friends and relatives that they either had not seen for a long time, or they met for the first time. Since then the contacts among friends and relatives continued, and when in 1990 living conditions in Bulgaria became extremely difficult, the inhabitants of Nea Messimvria sent a food mission to the Messimvrians in Bulgaria. But the recipients and the senders were not only those who stayed in Bulgaria then, or who left: in 1990 both groups included also the new relatives, friends, and neighbors that they acquired in the meantime.

Picture of Messimvrians of Nessebur. Message on back side: My dear sister, I send you a photograph. You don't have your eyes to see us; we also grew old. Your sister and your brother-in-law, Nikolas ![]()

This exhibition was initiated by the desire of people of Nea Messimvria, Greece, and of Nessebur, Bulgaria, to talk about this shared part of their lives called Messimvria. For people both in Bulgaria and in Greece, Messimvria constitutes a significant part of their identities, a common point of reference. Memories and stories about their past lives, photos of relatives, and pictures of Messimvria on the walls in every house testify the importance and the presence of the relationships with people and with objects, which do not belong to the past, but are part of an active present. The common places of memory become, for those who share them, open lines of communication between the past and the present, while they open up the way for the continuation of communication and the reformation of relationships in the future.

This exhibition was initiated by the desire of people of Nea Messimvria, Greece, and of Nessebur, Bulgaria, to talk about this shared part of their lives called Messimvria. For people both in Bulgaria and in Greece, Messimvria constitutes a significant part of their identities, a common point of reference. Memories and stories about their past lives, photos of relatives, and pictures of Messimvria on the walls in every house testify the importance and the presence of the relationships with people and with objects, which do not belong to the past, but are part of an active present. The common places of memory become, for those who share them, open lines of communication between the past and the present, while they open up the way for the continuation of communication and the reformation of relationships in the future. ![]()

FURTHER READING

As already mentioned, this WWW page is created for an audience of non specialists to the subject. The following titles can provide the reader with a wider ethnographic and historical knowledge of the studied case. No theoretical work related to the subject has been included.

Further reading on the exchange of populations between Greece and Bulgaria

Eddy C.B., 1931, "Greece and the Greek Refugees", G. Allen & Unwin Ltd., London.

Ladas S., 1932, "The Balkan Exchange of Minorities", McMillan Co, N.Y.

Pentzopoulos D., 1962, "The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and its Impact upon Greece", Mouton, Paris.

Further reading on Messimvria

Velkov V., 1989, "Nessebur", Sofia Books Press, Sofia.

Venedikov I. - Velkov V. and others, 1969, "Nessebre", Editions de l' Academie Bulgares des Sciences, Sofia.

Megas G., 1945, "Anatoliki Roumelia" (in Greek), Sillogos pros Diadosin ton Ellinikon Grammaton, Athens.

Konstantinidis M., 1945, "I Messimvria toy Efxeinou" (in Greek), Estia, Athens.

Kotzageorgi X., 1997, "Oi Ellines tis Voulgarias: Ena istoriko tmima tou Perferiakoou Ellinismou" (in Greek), Geniki Grammatia Apodimou Ellinismou, Athens.

Agelopoulos G., 1994, "Zontas Anamesa: Taftotita kai Politikes mias Chorismenis Koinotitas" (in Greek), Ethnologia, Vol. 2, pp. 147 - 163.

Further reading on mixed villages of Greek Macedonia

Agelopoulos G., 1997, "From Bulgarievo to Nea Krasia, From the "Two Settlements" to the "One Village": Community Formation, Collective Identities and the Role of the Individual", in P. Mackridge and E. Yanakakis (edit.) "Ourselves and Others", Berg, New York.

Boeshoten van R., 1993, "Politics, Class and Identity in Rural Macedonia: a Comparative Perspective" Paper presented at the conference "The Anthropology of Ethnicity: a Critical Evaluation", University of Amsterdam.

Brown K., 1993, "When Ink Trumps Blood: Nation and Identity in a Greek and Macedonian Family", Paper presented in the Modern Greek Studies Association International Symposium, Berkeley University, California.

Cowan J., 1997, "Idioms of Belonging: Multiethnicity and Local Identity in a Greek Town", in P. Mackridge and E. Yanakakis (edit.) "Ourselves and Others", Berg, New York.

1990, Dance and the Body Politic in Northern Greece, Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton N. J.

Damianakos S. - Nikolakopoulos I., 1978, "Vergina. Georgikos Eksichronismos kai Koinonikos Metaschimastismos" (in Greek), The Greek Review of Social Sciences, Vol. 33 - 34, pp. 432 - 478.

Danforth L.M., 1989, "Firewalking and Religious Healing", Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Danforth L.M, "The Macedonian Conflict. Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World", Princeton University Press, Princeton N.J., 1995.

Drettas J.G., 1977, "Les Notres": Un example de contacts interethniques en Macedoine, village de Hrisa", Etudes Balkaniques, Vol. 3, pp. 76 - 90.

Lafazani D., 1991, "Cultures frontalieres en Grece: la question sociale locale de la difference culturelle", Paper presented at the confernce "Cultures et regions transfontaliere en Europe a l' aube du marche unique", Colloque International de Geographie Politique, Andorre, 27 - 29 May 1991.